Roma have a new sporting director – Ramon Rodriguez Verdejo, more commonly known as Monchi.

The Spaniard has spent almost his entire working life at his local club, Sevilla, beginning there as a youth team player before really finding his calling as a sporting director after hanging up his boots.

In that role - the same one he now takes on with the Giallorossi - he helped establish the Andalucian club as one of the country’s most successful and competitive sides, while spotting and nurturing footballers that would go on to become the brightest lights of their generation.

Here are the key details you need to know about the 48-year-old.

1. He's the local boy done good...

Ramon Rodriguez Verdejo was born in San Fernando, near Cadiz, in 1968. Around two hours’ drive up the E-5 from Seville, his exploits as a teenage goalkeeper saw him brought into the Rojiblanco youth academy, where he would show a certain amount of promise – promise he would try to make the most of with a commitment to hard-work and self-improvement that impressed his coaches.

He followed the route of a lot of young Spanish players of that time – making his debut for Sevilla B during the 1988-89 season, and learning his trade at that level before finally being promoted to the first-team squad in summer of 1990.

2. He suffered a painful injury on his debut

Twenty-two before he made his full senior debut for Sevilla, Monchi would – by his own acknowledgement – never really move beyond the role of reliable, if rarely-utilised, back-up goalkeeper.

The man himself would become somewhat dismissive of his playing days, amusingly describing his place in the squad as “the last monkey: a 23-year-old sub goalkeeper” in a recent interview. His debut, in 1991, was notable mainly because he dislocated his finger almost immediately – refusing to be substituted as he suspected the opportunity to play was one he might not get again for a while.

3. During a 10-year career he was almost never a starter...

Generally a back-up goalkeeper throughout his career, only briefly did he endure a sustained run of games in the first-team – usually when injury or suspension befell the No. 1.

In total he played 85 games over nine years, 20 of them coming in his final season, as he helped Sevilla back into La Liga at the end of the 1998-99 campaign.

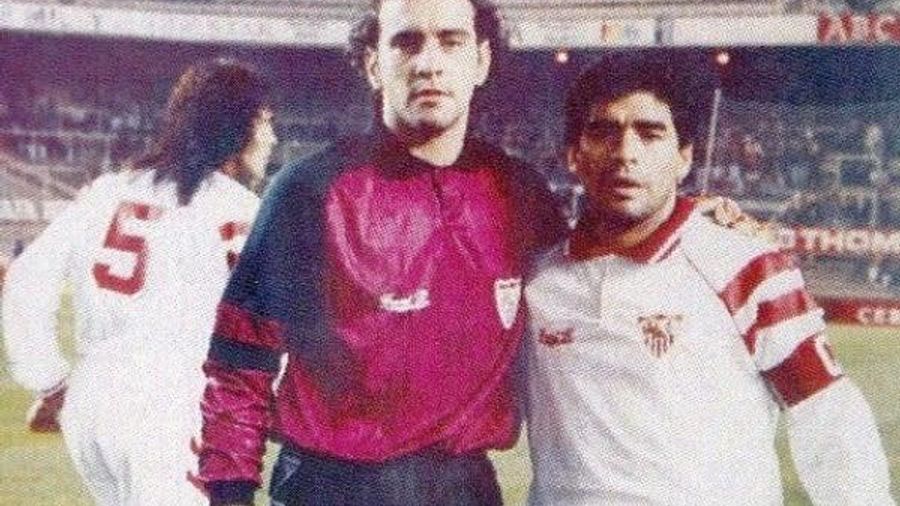

4. His watch? He got it from Maradona...

Part of that period was spent in the company of a certain Diego Maradona, where Monchi’s qualities as a director would perhaps first show their head. Of limited use on the pitch, the local boy would serve as an invaluable sounding board and confidante for the club’s most important talent.

Mobbed wherever he went, Maradona took to taking early morning walks around Seville to clear his head. Monchi - never much of a sleeper - would join him, the pair striking up a close relationship.

“He was a 10 out of 10 as a person,” Monchi later told the Guardian. “… and a 20 out of 10 as a player.”

Once, Maradona commented – perhaps jokingly – about Monchi’s watch, a ‘Rolex’ that the wearer would quickly admit was a fake. Before he left the club, the Argentine presented Monchi with a brand new Cartier – a token of his respect and appreciation for a man who had little to offer him in a conventional footballing sense.

Perhaps aware of his limitations as a top-flight goalkeeper, after helping his team to promotion Monchi chose to hang up his gloves.

Within a year he would step into an entirely different role, one that would make him entirely more pivotal to the club he loved.

5. From goalkeeper to sporting director in record time

In 2000, with Sevilla having been relegated to the Segunda for a second time and in something of a crisis, the club turned to Monchi to steer them through a tumultuous period – with the ex-goalkeeper initially working as the team delegate (managing matchday formalities and the like) before quickly being moved into a sporting directorship role.

The club were promoted as champions in his first season in management – a not unexpected development – but the mandate was to ensure that a third drop to the second tier would not occur.

6. He believes in homegrown talent as much as transfer market moves

Monchi went about achieving that in two ways: by bringing in raw talent on one hand, and nurturing the club’s academy graduates on the other. While the emergence (and subsequent sale) of stars like Dani Alves, Julio Baptista and Seydou Keita would come to define Monchi’s reputation, in the early years it was the faith shown in the likes of Jose Antonio Reyes, Sergio Ramos and Jesus Navas (all homegrown talents) that enabled Sevilla to show such progress.

In their first season back in La Liga, with Reyes a teenage influence, they finished eighth. The next season they finished ninth. The following year, with Alves, Reyes, Ramos, Baptista, Antonio Puerta and more increasingly established in the first team squad, they finished sixth – the start of a seven-year run inside the top-six of La Liga.

And then the trophies – for a club that hadn’t even won one since 1948 – would start to flow.

7. He knows how to replace stars...

By the time Sevilla won the first of five Europa League titles, in 2006 (when the competition was still known as the UEFA Cup), the club had become a target for bigger clubs keen on their brightest talents. Reyes (to Arsenal) and Sergio Ramos (Real Madrid) had been sold, with the likes of Luis Fabiano and Frederic Kanoute coming in to refresh the side.

This would become a familiar motif, as Sevilla won with one squad, sold some of their most in-demand talents to European heavyweights, and then brought in new talent that would seemingly step in without missing a beat. In the last decade of Monchi’s reign the club would only finish outside the top seven twice (and never outside the top 10), despite the quality of La Liga and the loss of players of the ability of Alves, Ivan Rakitic and so, so many more.

8. He speaks four languages ... and scouts 250 players at a time

Monchi, who speaks Spanish, French and English fluently and is rapidly adding Italian to that list, has often given an insight into his approach to identifying and signing new talent. At Sevilla he had nearly 20 scouts watching games around the globe (some reports have put his network of ‘informants’ in the hundreds), while he himself would watch as many as 10 games a weekend.

From that he would keep an updated list of around 250 potential transfers, in all positions and with a range of degrees of interest. From there he would close in on specific targets as his manager required, removing some when negotiations became too complex (or expensive) and continuing further with those that fit the parameters for all parties.

This constantly expanding and deepening scouting network ensured Sevilla could react to replace any player in their squad, and would prove a key reason the club could continue to contend on all frontiers for more than a decade despite annual ins and outs.

Over his 17 years he signed more than 150 players, the vast majority of whom would go on to prove great successes.

9. He won nine trophies at Sevilla

Monchi’s consistent record of transfer success earned him a reputation as a master in trading, a calling card that came to overshadow everything else. He would come to be asked almost solely about his market approach in interviews, and in essence one key question: whether he preferred buying players at a bargain price or selling them at a huge profit.

He was always insistent. “Neither,” he’d correct. “The priority is to win trophies.” In that regard he hit the mark as well.

After winning the Copa del Rey in 1948, Sevilla did not win another major honour in the more than 50 years before Monchi took over. In just over five the man had helped change that, as the club won the UEFA Cup against Middlesbrough in 2006.

Four more UEFA Cup/Europa League successes would follow over the next decade, along with two Copa del Rey wins and two successes in the Super Cups those victories qualified Sevilla for – the Spanish Supercopa and the European Super Cup.

Most recently, Sevilla have won the Europa League in each of the last three seasons (an unmatched achievement in European football history). The club that couldn’t win anything for almost six decades suddenly could not stop acquiring trophies - nine in total under Monchi's direction.

10. He left Sevilla a lion - and arrives at Roma with hunger to succeed

Unsurprisingly, then, Monchi was afforded a grateful farewell from the club when, earlier this year, he announced his decision to leave in search of a new challenge.

Presented on the pitch at the Ramon Sanchez Pizjuan with the trophies won during his tenure, Monchi wore a Sevilla shirt with ‘Puerta 16’ on the back, a tribute to Antonio Puerta – an club academy graduate who sadly died on the pitch during a match in 2007.

“No-one takes a ‘what great economic results’ banner to the stadium,” Monchi once joked, and on this day he was proven correct - instead the nine major trophies his teams won (along with a few prestigious awards they also received) were paraded and applauded.

Hailed as a ‘lion’ of the club – indeed, his Twitter handle contains that moniker – the man was in tears as both parties wished a fond and thankful farewell.

Now he comes to Roma, hoping to build a similar legacy.

"I won’t rest, even for a second, until we’ve achieved all the aims we have in mind," he said.

Tickets

Tickets

Shop

Shop